If you're interested in making a DIY resistor calibration board using discarded resistors, this article might be worth a look.

If your meter can only read down to 0.1 ohms, then even if the calibration board looks like it's an integer value, a higher-precision meter will still show that the numbers aren't accurate. So during the process, you can use a more accurate meter. If you want precision down to four decimal places, that's easy too—just experiment with the enameled wire a few more times.

Compared to a resistor calibration board, a capacitor calibration board is even less accurate. Different devices and different frequencies give completely different readings, and capacitor characteristics themselves introduce a lot of uncertainty—tantalum capacitors included. But for resistors, as long as they're not heavily oxidized, their resistance stays stable for a long time, making them ideal for an entry-level calibration board.

If you're interested, keep reading.

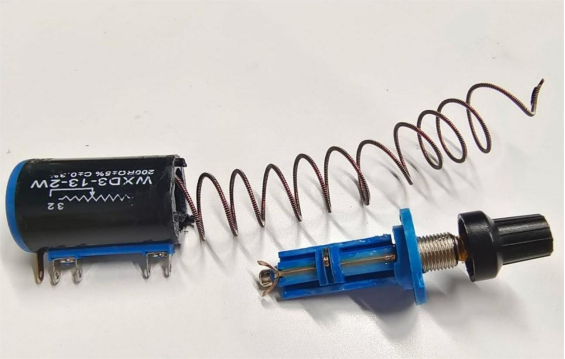

For this DIY project, the discarded resistor you'll need is the adjustable resistor shown below. Even after all kinds of adjustments, the resistance still jumps randomly when you turn the knob. My guess is that the threaded structure is loose (the movable contact doesn't touch the thread well, the thread itself is soft with no elasticity, and it doesn't make solid contact with the plastic tube wall, leaving gaps). When taken apart, it looks like the picture below.

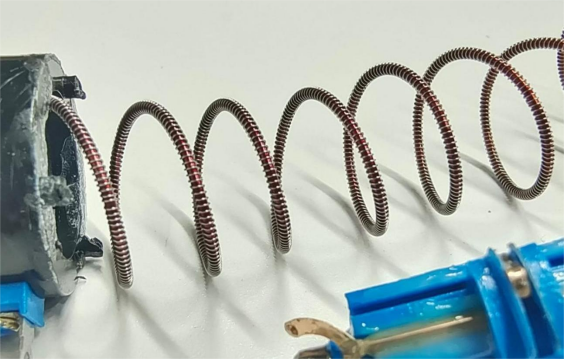

Zooming in, you can see the resistance wire wrapped around a spiral frame. The frame should also be metal, but coated with insulating varnish.

The material is extremely soft—probably pure aluminum—and has almost no elasticity, causing the spiral body to fail to press firmly against the resistor tube wall.

The resistance jumps up and down with no pattern at all.

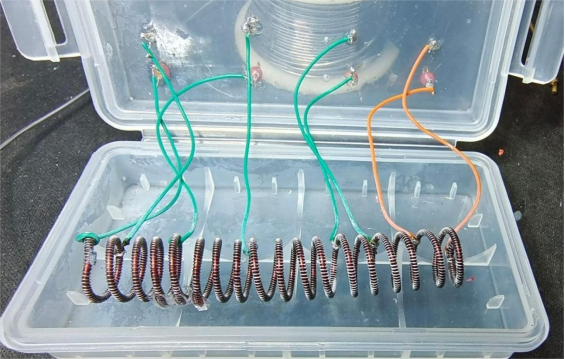

After completely disassembling it, you need to measure the entire resistance from one end to the other with a multimeter, then solder using OK wire. Here's something to keep in mind: the resistance you choose should be slightly under the target value. For example, if you want 50 ohms, make sure the value is as close as possible to 50 but less than 50.

If it's lower, you can compensate. If it's higher, you're stuck. The one disassembled here is 200 ohms (you can use 100K or even larger).

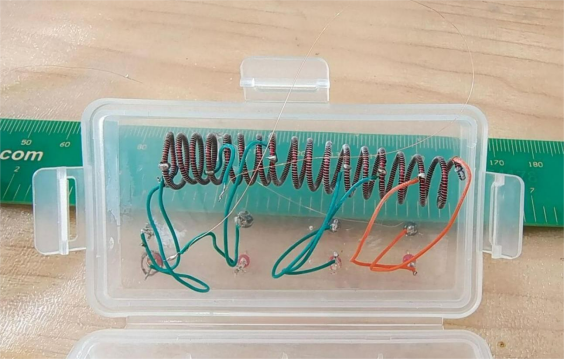

You can break it into segments like this: 10 ohms, 50, 100, 150, 175, 200, and 222 ohms.

Also, resistance wire doesn't take solder well, so you'll need to wrap it several times and then apply solder to cover it. Don't keep heating the plastic case too long, or it'll deform.

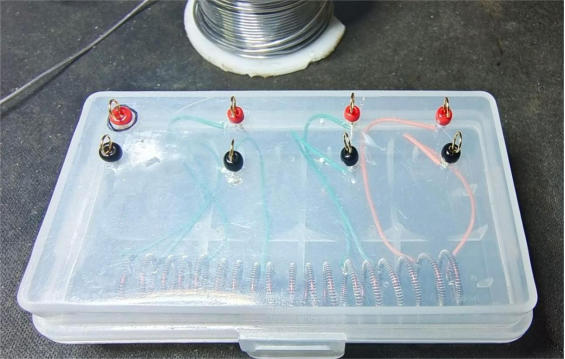

You can use a box like the one below. If you have more ideas later, you can even add a row of capacitors—there's plenty of room. As shown below, those red and black things on the case are test points—test beads or gold-plated ceramic rings used for PCB test pins.

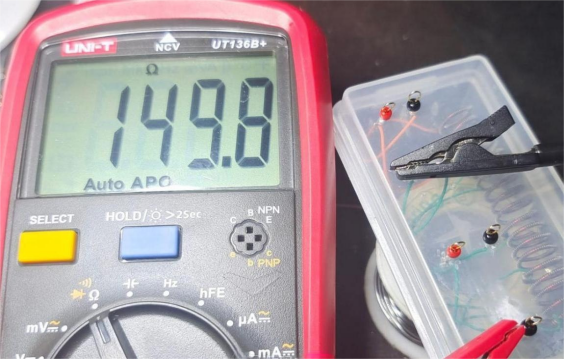

After soldering everything, you can start testing. As you can see in the picture below, each value is close to—and slightly under—the target value.

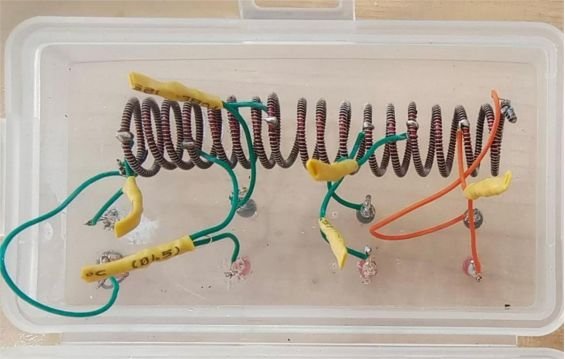

Now let's do the precision compensation. You'll need some 0.01 wire. The thinner the wire, the higher the resistance, and the material matters a lot too. You can use paint-free enamel wire, which can be soldered directly. Depending on the thickness and material, the resistance will vary. Just take a ruler and measure it yourself. The wire shown below is 20 cm long; with a quick calculation you can figure out the resistance and length you need. The spool shown comes out to roughly 0.5 ohms per 12 cm.

Once you've calculated the length, you can start soldering.

Then you'll need to measure the resistance again. Once it hits your target, you're good to go.

The wire in the picture below is pretty obvious, and it's short—about 0.2 ohms.

Finally, tidy up the wire, add heat-shrink tubing, and you're done.

End.