In the electronic components industry, thermocouples are widely used temperature sensors that attract significant attention from engineers and technicians. Whether in industrial control, automotive manufacturing, or scientific research, thermocouples play a critical role. Understanding the basic laws of thermocouples not only improves equipment efficiency but also helps optimize the entire measurement system. This article will provide a detailed overview of thermocouples, including their definition, working principle, features and advantages, and will focus on explaining the four fundamental laws of thermocouples.

Catalog

IV. The Four Fundamental Laws of Thermocouples

2. Intermediate / Middle Conductor Law

3. Intermediate Temperature Law

4. Reference Electrode / Reference Junction Law

I. What is a Thermocouple?

A thermocouple is a temperature sensor based on the thermoelectric effect and is composed of two different metals or alloy wires joined together. When the two junctions of a thermocouple are at different temperatures, an electromotive force proportional to the temperature difference is generated, enabling precise temperature measurement. These sensors are simple in structure, cost-effective, and suitable for extreme environments, which is why they are widely used in the electronic components industry—for example, in high-temperature furnaces, power systems, and household appliances.

II. Work Principle

The working principle of a thermocouple primarily relies on the Seebeck effect, which states that a voltage is generated in a circuit when two different conductors have junctions at different temperatures. Specifically, a thermocouple has a hot junction and a cold junction: the hot junction is exposed to the temperature being measured, while the cold junction maintains a reference temperature. The temperature difference causes electrons to move between the metals, generating a voltage signal. This signal can then be converted into a temperature reading by measuring instruments. Since this process does not require an external power supply, thermocouples are highly advantageous for remote monitoring and automated systems.

III. Features and Advantages

Thermocouples offer a range of features and benefits, making them a preferred choice for temperature measurement. First, they respond quickly, allowing real-time capture of temperature changes, which is ideal for dynamic environments. Second, their operating temperature range is broad, from hundreds of degrees below zero to over a thousand degrees Celsius, covering most industrial needs. Additionally, thermocouples are robust and durable, resistant to vibration and corrosion, and have a long service life. Their output signals are stable and accurate, and their relative low cost makes them suitable for large-scale applications.

IV. The Four Fundamental Laws of Thermocouples

Next, we will examine the four fundamental laws of thermocouples. These laws form the foundation for understanding and applying thermocouples, covering their physical characteristics, environmental adaptability, and measurement accuracy.

1. Homogeneous Conductor Law

The Homogeneous Conductor Law states that a closed circuit made of a single homogeneous conductor, regardless of cross-sectional uniformity, will not produce a net electromotive force even if a temperature gradient exists along the conductor. This law is a fundamental premise of thermoelectric measurement. In practice, it means that each thermoelectric element of a thermocouple must be uniform. If the material becomes locally contaminated, oxidized, or stressed, parasitic voltages can arise in the non-uniform regions, introducing measurement errors. Therefore, it is essential to ensure the homogeneity of thermocouple wires and avoid excessive mechanical stress during installation.

2. Intermediate / Middle Conductor Law

The Intermediate Conductor Law is key to applying thermocouples in real circuits. It states that in a thermocouple circuit made of conductors A and B, the insertion of a third conductor C will not affect the total electromotive force of the circuit as long as both ends of C are at the same temperature. This law allows the safe introduction of measuring instruments (like voltmeters), connecting wires, and terminals into the thermocouple circuit without adding extra error. As long as these intermediate conductors have both ends at the same temperature—typically ambient—the measurement reflects only the temperature difference between the hot and cold junctions.

3. Intermediate Temperature Law

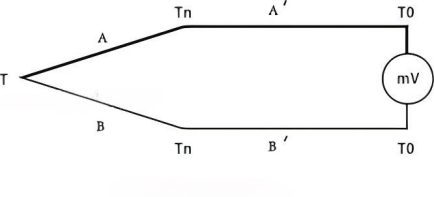

In a thermocouple measurement circuit, if the measuring end is at temperature T and the connecting wires have temperatures Tn and T0 at their respective ends, and if the thermoelectric properties of electrodes A′ and A, B′ and B are identical, the total electromotive force equals the algebraic sum of the thermocouple’s EMF EAB(T, Tn) and the connecting wire's EMF EA′B′(Tn, T0). In other words: EABB′A′(T, Tn, T0) = EAB(T, Tn) + EA′B′(Tn, T0), Under this condition, the total measured EMF is influenced only by the measuring end temperature T and the environmental temperature T0, regardless of changes in the reference junction temperature Tn.

The Intermediate Temperature Law is the theoretical basis for using compensation wires. By employing wires with the same thermoelectric properties as the thermocouple, the reference junction can be positioned away from the heat source without affecting measurement accuracy.

4. Reference Electrode / Reference Junction Law

The Reference Electrode Law greatly simplifies the creation of thermocouple tables. It states that if the EMF of thermocouples made of conductors A and C relative to a reference electrode B (usually pure platinum) is known, then the EMF of a thermocouple made directly from A and C equals the algebraic sum of the two EMFs.

This law eliminates the need to experimentally calibrate every possible material combination. By calibrating all thermocouple materials against a standard platinum wire, a comprehensive database can be established, allowing calculation of the EMF-temperature relationship for any material pair—greatly improving efficiency and ensuring data consistency.

Besides understanding these four laws, practical applications require considering other factors. Different thermocouple types (like K, J, S, B) have different measurement ranges, sensitivity, stability, and suitable environments due to their materials. For example, K-type thermocouples (Nickel-Chromium/Nickel-Silicon) are widely used for their cost-effectiveness and wide temperature range, while S-type thermocouples (Platinum-Rhodium 10/Platinum) are used in higher-temperature, oxidative environments. Installation methods (threaded or flanged), protective sheath material selection, and electromagnetic interference protection are all key to ensuring long-term stability and reliability.

V. Conclusion

The four fundamental laws of thermocouples—from the basic requirement of homogeneous conductors, to the allowance for intermediate conductors, the method for calculating intermediate temperatures, and the simplification via reference electrodes—together form a rigorous and practical theoretical system. Mastering these laws is crucial for thermocouple material selection, wiring layout, system calibration, table application, cold-junction compensation, and error control.